The hot talk in Washington is about inflation, not interest rates. “We’re experiencing a big uptick in inflation, bigger than many expected, bigger certainly than I expected, and we’re trying to understand whether it’s something that will pass through fairly quickly or whether, in fact, we need to act,” Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell told the Senate Banking Committee last week.

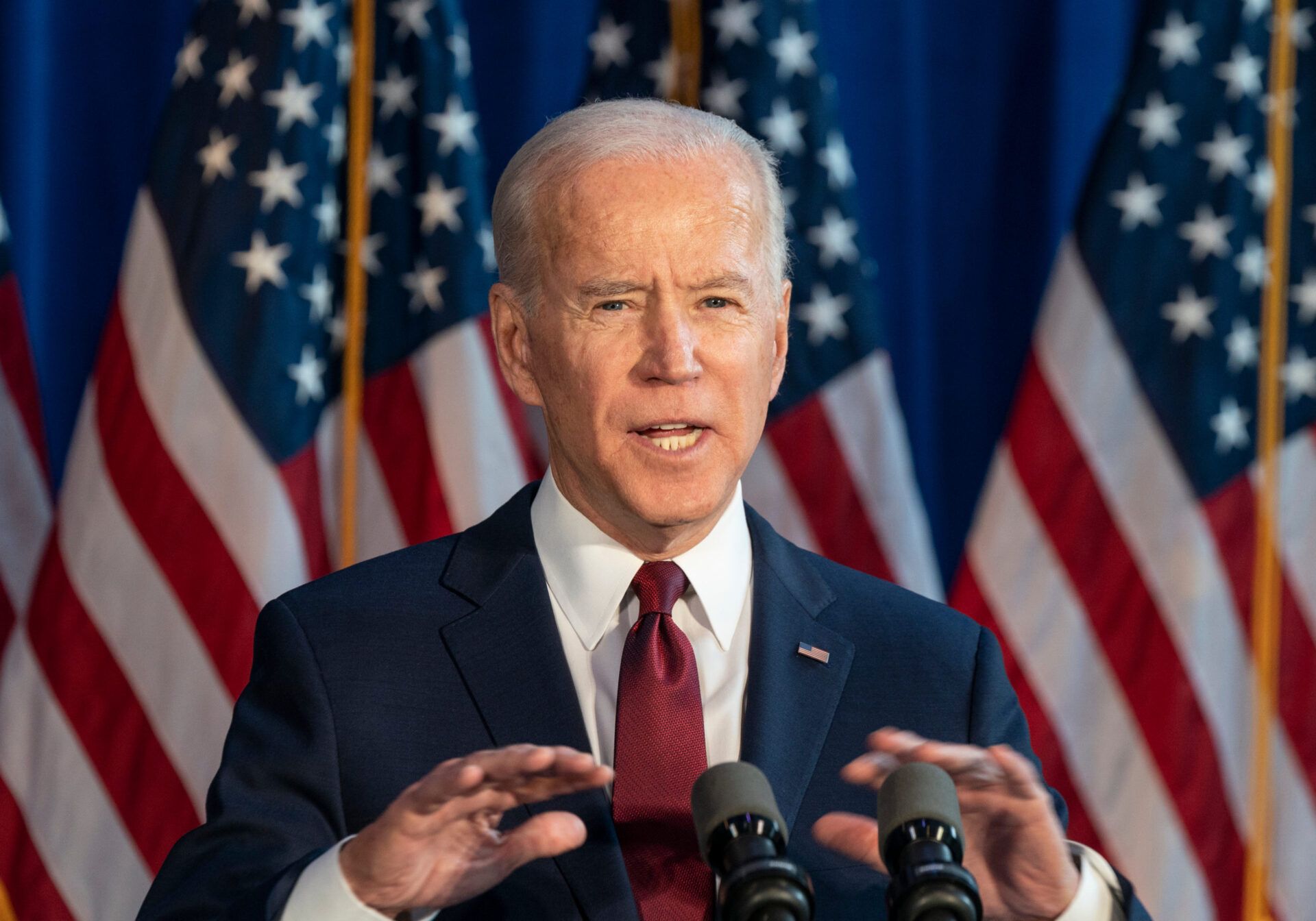

Meanwhile, U.S. mortgage interest rates have risen since President Joe Biden took office in January according to Federal Reserve data. On the day he was inaugurated, the 30-year fixed rate was around 2.75 percent. By April 1, it had risen to 3.18 — its highest level since June of last year. Rates have been gradually declining since then but have remained elevated over their recent pre-Biden numbers.

Higher rates could be an indicator of an economy recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic, a welcome political boon for the Democratic president during his first year in office. However, even higher rates could be a sign inflation is an impending problem, with higher prices heading into 2022 — an election year.

Could higher rates today actually be an economic boon tomorrow? Biden insists that inflation isn’t a problem. “There’s nobody suggesting serious inflation is on the way. No serious economist,” he said at Monday’s press conference. But just four days earlier, his own Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen predicted, “I think we will have several more months of rapid inflation.”

As far as higher interest rates, Yellen said last month they could be a plus. “If we ended up with a slightly higher interest rate environment it would actually be a plus for society’s point of view and the Fed’s point of view,” Yellen told Bloomberg.

Still, the counterintuitive boon of higher rates could be overshadowed by other chronic problems facing the housing market, issues that threaten to drag out recovery and create potential long-term broader economic issues.

The National Association of Home Builders, for instance, noted recently that homebuilder confidence is slipping due to ongoing concerns over high material prices. Builders “are contending with shortages of building materials, buildable lots and skilled labor as well as a challenging regulatory environment,” the group said.

A slowdown in housing construction, if it occurred, could harm the overall economy if more buyers get priced out of the market.

Even as houses continue to get built, data indicate just one percent of new housing could be considered low-cost in the present market, priced between $100,000 and $150,000. That math is effectively excluding the 25 percent of house hunters looking for cheaper options. It could be a political albatross around the neck of a Democratic administration that ran aggressively on a platform of middle-class support.

Overall, the post-pandemic economic landscape is riddled with uncertainties, some of them new and others—like the country’s current battle with inflation—more familiar but exacerbated by the health crisis. Diane Swonk, the chief economist with the firm Grant Thornton, told The Washington Post this week the COVID-19 crisis has been “a once-in-a-century experience with a different economy than it was a century ago. There’s just no road map.”

Biden has pledged to use the federal government to help middle-class homeowners purchase their first homes, meaning the administration has likely been prepping for plans to address these and other issues. Still, the White House will have to act deftly to ensure economic forces outside its control don’t hobble its broader recovery efforts just a few months into Biden’s first term.