The most important question about the federal government’s latest nationwide ban on evictions isn’t whether it’s the right thing to do or whether it will even accomplish much—it’s whether or not it’s actually legal.

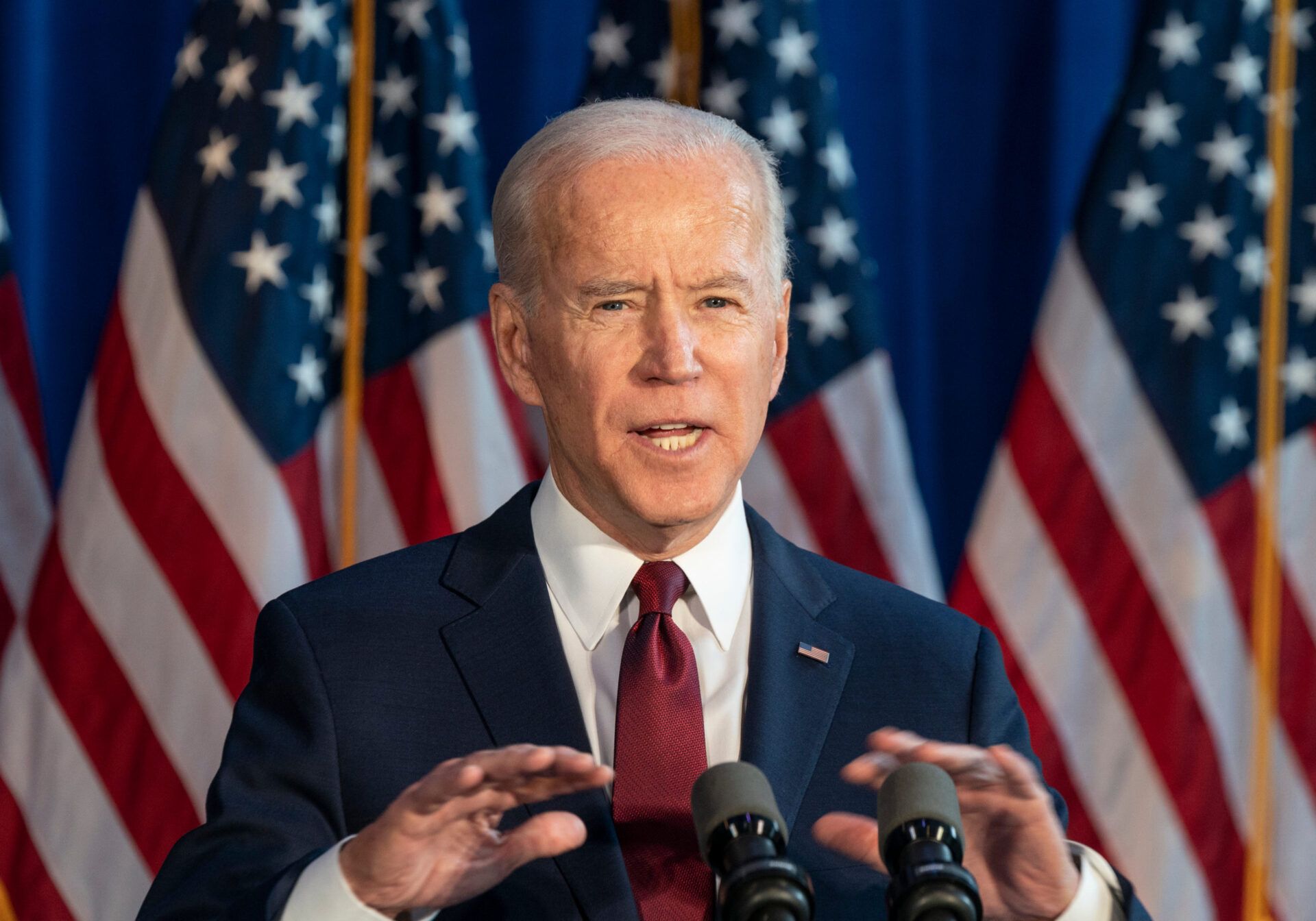

Tellingly, President Joe Biden himself doesn’t seem to have much faith that it is, a sign that the current administration considers the move less a practical solution and more a political feint or strategy.

The federal eviction moratorium was first put in place last year. But it was done so via the executive branch—specifically the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—rather than Congress.

That distinction is critical. The Supreme Court has decided over several decades that Congress, under the U.S. Constitution, has fairly broad latitude to legislate on matters of national importance. The White House—and the federal agencies that exist under the White House, including the CDC—have some ability to issue rules and regulations to a similar effect, though that ability is far more constrained than that of Congress.

Those constraints were noted in a Supreme Court ruling in June on the original moratorium, where Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote the CDC “exceeded its existing statutory authority by issuing a nationwide eviction moratorium,” and that “clear and specific congressional authorization (via new legislation) would be necessary for the CDC to extend the moratorium.”

Legal scholars have similarly argued the measure was extralegal. Allowing such directives to stand “would give the CDC authority over huge swaths of our economy to avoid even the possibility of the ‘introduction’ or spread of a disease,” George Washington University law professor Jonathan Turley wrote on the moratorium.Assumption University political science professor Greg Weiner, meanwhile, wrote in The New York Times the latest ban was “troubling and bizarre” and that the U.S. is maintaining “the empty shell of the separation of powers around the core of a partisan system.”

Yet the most surprising source of doubt over the new moratorium came from Biden himself. “The bulk of the constitutional scholarship says that it’s not likely to pass constitutional muster,” he admitted upon the issuance of the order, though he argued that, “at a minimum,” the directive would “give some additional time” for the government to distribute rental assistance ahead of the ban’s potentially being struck down.

At the center of this swirling political mess—a president who doubts his own administration’s order, legal scholars who say it’s not likely to pass, and a Supreme Court that has already all but ruled against it—are American renters, homeowners, and landlords, who for months now have existed under a regime of uncertainty where it’s unclear if and when the rent will be due.

Answering that question one way or the other is going to be a political headache for the Biden administration; perhaps one reason, among many, that the White House would prefer to extend the ban for as long as it feasibly can.